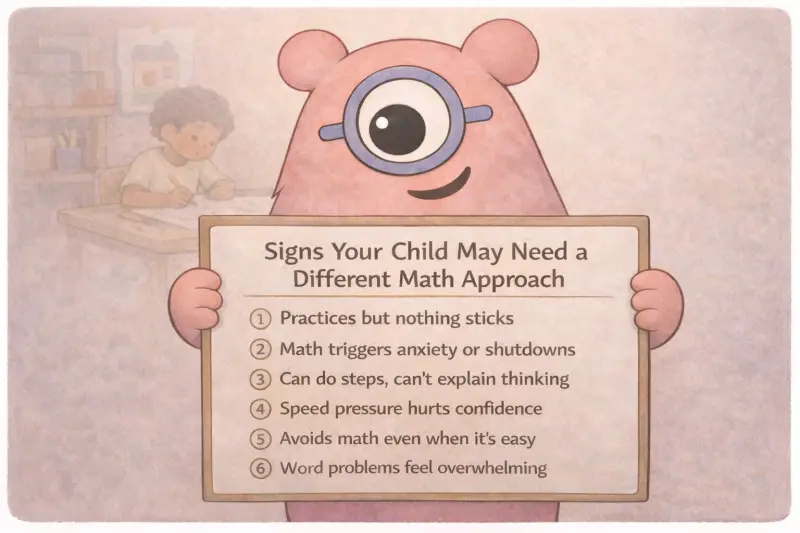

Signs Your Child Needs a Different Math Approach (Not More Practice)

TL;DR

If your child practices but doesn’t retain, they may be overloaded or missing conceptual foundations.

If math triggers shutdowns, tears, or avoidance, anxiety may be blocking working memory.

If they can do steps but can’t explain, they may be relying on fragile procedures.

If speed is emphasized, performance pressure can reduce accuracy and confidence.

If word problems feel impossible, executive-function load may be the bottleneck - not intelligence.

In many cases, a visual, strategy-first, low-pressure approach helps more than extra practice.

If your child keeps practicing math but doesn’t seem to improve - or if math is turning into a daily stress-fest - it’s natural to think, “Okay… we just need more practice.”

But here’s the catch: when practice isn’t working, the problem is often the approach, not the number of problems.

In learning science, repeated drills can backfire when they overload working memory, reinforce fragile procedures, or intensify anxiety - all of which can make math feel harder over time. That’s why a “do more of the same” plan sometimes leads to the opposite outcome: less confidence, more resistance, and slower progress.

Below are research-backed signs your child may need a different math approach (more visual, more strategy-based, more supportive), not more worksheets.

1) They Practice a Lot - But Nothing Seems to Stick

Your child does the homework. You add extra worksheets. Maybe you even try summer packets or tutoring. Yet every new unit feels like starting over.

This can happen when practice is heavily procedural (repeat these steps) without building the mental “why” behind it. When children don’t have stable schemas, more problems can demand more working memory than they have available - something explained in Sweller’s cognitive load research.

In plain language: if a task is eating up a child’s mental bandwidth, they may not have enough capacity left to actually learn from it.

If this sounds familiar, the “fix” is often to shift from more repetition to more representation (ten-frames, number lines, arrays, drawings), then return to practice once concepts feel stable, because visual math strategies offload working memory and support deeper conceptual understanding.

2) Math Triggers Tears, Anger, or “I Can’t” Shutdowns

If math routinely ends in tears, yelling, stomach aches, or total refusal, that’s not a motivation problem. That’s your child’s nervous system saying, “This feels unsafe.”

Math anxiety is strongly linked to worse math performance, in part because anxiety competes for the same limited working memory resources needed to solve problems.

And this isn’t just an “older kids” issue. In children, research also finds meaningful links between math anxiety, working memory, and later achievement.

When anxiety is present, “more practice” can become “more threat.” Often, the most productive move is to change the experience: smaller steps, more visuals, no time pressure, and a focus on sense-making.

3) They Can Follow Steps - But Can’t Explain Their Thinking

Some kids can produce correct answers… until the problem looks slightly different. Then it falls apart.

This often happens when children are relying on procedures without conceptual grounding. Research on the relationship between conceptual and procedural knowledge suggests that durable learning involves building both - and that they support each other over time.

A simple “tell” is what happens when you ask, “How did you get that?” If the answer is:

“I don’t know.”

“I just did it.”

“That’s the rule.”

…then the next step is often not more problems - it’s more meaning. Encourage explanations with drawings, number lines, ten-frames, and “show me in a picture” prompts. That kind of external thinking reduces working memory load and strengthens understanding.

4) Speed Is the Main Goal (And Your Child Is Slowing Down)

If your child’s math world is full of timers, mad-minutes, speed races, and “faster is smarter” messaging, it can quickly create performance pressure.

Under high pressure, even students with strong working memory can perform worse than expected, effectively “choking,” because the pressure reduces the cognitive advantage their working memory normally provides.

Timed conditions can also change performance patterns in children in ways that matter - research shows that under time pressure, children with higher levels of math anxiety tend to perform worse on math tasks compared with untimed conditions, suggesting that timing can exacerbate anxiety and hinder accuracy.

This doesn’t mean all timed activity is “bad.” But if your child’s confidence collapses when speed is emphasized, it’s a sign the approach needs adjustment: prioritize strategy, visual reasoning, and accuracy first - then build efficiency gradually, without threat.

5) They Avoid Math Even When It’s Not “That Hard”

A lot of parents find this confusing: “They can do it… so why are they refusing?”

Avoidance is often a learned response to repeated stress. If math has become associated with embarrassment, overload, or conflict, your child may avoid it even at easier levels because the emotional memory is still there.

This is especially common in ADHD learners, where attention, emotion regulation, and learning demands interact. Classroom-based research drawing on the perspectives of students and teachers highlights the importance of reducing overload and using structured supports to help children stay engaged and on task.

In practical terms: the goal isn’t “force compliance.” The goal is “make math feel doable again.” Short sessions, predictable routines, visual scaffolds, and success-first sequencing can be game-changing.

6) Word Problems Are a Disaster (Even If They Can Calculate)

Word problems are not “just math.” They require language processing, attention control, planning, and holding multiple pieces of information in mind - all at once.

For many capable kids, the challenge isn’t calculation but understanding the language and structure of the problem, and small changes in how problems are approached can significantly reduce overwhelm.

If your child melts down at multi-step word problems, consider shifting the approach to reduce EF load:

Use visual schemas (“What do I know? What do I need?”)

Draw the situation (bar models, tape diagrams, quick sketches)

Highlight quantities and relationships before calculating

Let them explain verbally before writing

This is a case where “more practice” without structure usually just means “more overwhelm.”

What a “Different Math Approach” Usually Looks Like

When parents hear “different approach,” they sometimes worry it means lowering standards. It doesn’t. It means changing the path so your child can actually access the learning.

Across research on cognitive load, anxiety, and conceptual development, a common pattern emerges: kids do better when math is designed to be visible, strategic, and emotionally safe.

That often includes:

Visual models (ten-frames, number lines, arrays, area models)

Explicit Strategy instruction for addition/subtraction and multiplication/division (making 10, near doubles, breaking apart numbers)

Low-pressure practice (no speed races as the main measure of “good at math”)

Short, consistent sessions (to reduce avoidance and build trust)

Immediate feedback that feels informative, not judgmental

FAQs

How do I know if my child needs more practice or a different approach?

If your child is practicing consistently but (1) not improving, (2) becoming more anxious, or (3) can’t explain their thinking, those are strong signals the approach needs to change before adding more practice.

Is this just a confidence issue?

Confidence is often the outcome, not the cause. When math overload or anxiety blocks working memory, performance drops - and confidence drops right after. Addressing the learning experience usually improves confidence as a side effect.

Are timers always harmful?

Not always. But if speed pressure consistently reduces accuracy, increases stress, or causes shutdowns, it’s a sign to shift toward untimed, strategy-based learning while rebuilding fluency gradually.

What if my child is “smart” but still struggles in math?

That’s common. Math demands working memory, executive function, and conceptual understanding. A child can be bright and still struggle if the approach is heavy on procedures, speed, or multi-step load without supports.

What’s one change I can try this week?

Pick one concept (like addition within 20) and switch from symbols-first to visuals-first: draw it, use a ten-frame, or use a number line. Ask, “Can you show me what’s happening?” before asking for the answer.

References

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Ashcraft, M. H., & Krause, J. A. (2007). Working memory, math performance, and math anxiety. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03194059

Pellizzoni, S., et al. (2021). The interplay between math anxiety and working memory on math achievement. Frontiers in Psychology (PMC full text). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9304239/

Smeding, A., Darnon, C., & van Yperen, N. W. (2015). Why do high working memory individuals choke? An examination of choking under pressure effects in math from a self-improvement perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 176–182.

https://pure.rug.nl/ws/files/90030598/Why_do_high_working_memory_individuals_choke._An_examination.pdfCaviola, S., Carey, E., Mammarella, I. C., & Szűcs, D. (2017). Stress, time pressure, strategy selection and math anxiety in mathematics: A review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1488.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01488/fullRittle-Johnson, B., & Schneider, M. (2015). Not a One-Way Street: Bidirectional Relations Between Procedural and Conceptual Knowledge of Mathematics. Educational Psychology Review.

https://www.unitrier.de/fileadmin/fb1/prof/PSY/PAE/Team/Schneider/Rittle-JohnsonEtAl2015.pdfMcDougal, E., Tai, C., Stewart, T. M., Booth, J. N., & Rhodes, S. M. (2022). Understanding and supporting attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the primary school classroom: Perspectives of children with ADHD and their teachers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(9), 3406–3421

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10465390/

Comments

Your comment has been submitted