How Parents Accidentally Increase Math Anxiety in Kids

TL;DR: Kids don’t just “get” math anxiety at school - home messages shape it too. Parents often accidentally increase math anxiety by

(1) modeling stress

(2) over-correcting mistakes

(3) emphasizing speed and performance

(4) using fixed-mindset language

(5) getting intrusive during homework help

(6) sending subtle stereotype signals, and

(7) turning homework into a high-pressure relationship moment.

Research consistently links math anxiety with lower achievement and avoidance, so reducing pressure at home matters.

Most parents don’t mean to make math stressful. You’re trying to help. You’re trying to protect your kid from struggle. You’re trying to keep them on track. And yet… some of the most common “helpful” moves at home can unintentionally crank up math anxiety.

Math anxiety is real, common, and powerful: large meta-analyses show a reliable negative relationship between math anxiety and math achievement, across ages and settings. That’s not because anxious kids are “bad at math.” It’s because anxiety steals attention and working memory resources right when kids need them most, and it can also push kids to avoid practice and challenge over time.

Below are the biggest ways parents accidentally raise math anxiety - and what to do instead.

1) Accidentally modeling math stress (even in small ways)

If you tense up, sigh, say “Ugh, I hated fractions,” or joke “I’m not a math person,” your child learns something important: math is a threat.

This isn’t just a vibe - research has found an intergenerational effect where parents’ math anxiety predicts children’s math outcomes, especially when math-anxious parents frequently help with homework. In a well-known longitudinal study, parents’ math anxiety was linked to children learning less math and developing more math anxiety when parents helped often.

Try instead: Aim for calm neutrality. You don’t have to pretend you love math - you just want your child to feel safe around it. If you catch yourself saying “I’m bad at math,” swap it for “I’m still learning this too.”

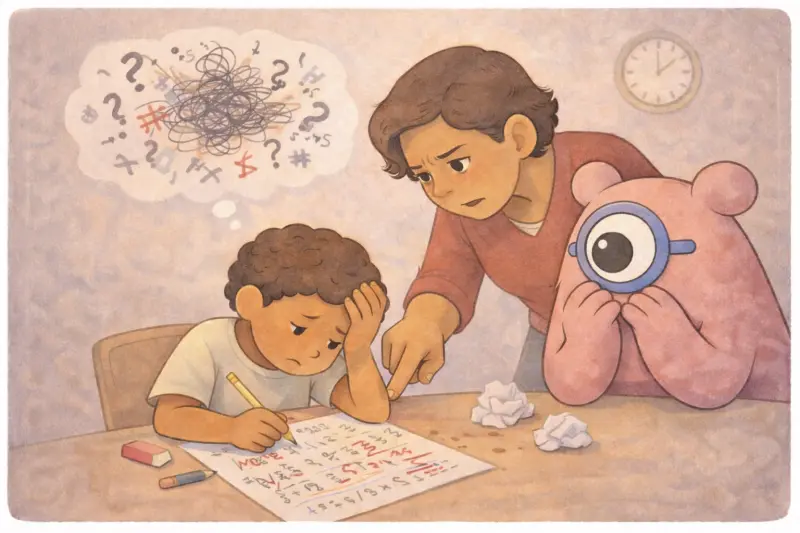

2) Over-correcting mistakes (and turning math into a judgment zone)

Many kids don’t fear math - they fear what math means: being wrong, being judged, disappointing someone, or “proving” they’re not smart.

When homework becomes a constant stream of corrections (“No, not like that.” “That’s wrong.” “How many times have we done this?”), kids learn that math is where you get evaluated. That evaluation pressure is one of the reasons anxiety hits working memory so hard - classic work in the field explains how worry and intrusive thoughts can compete with the mental resources needed for calculation and problem solving.

Try instead: Treat mistakes like information, not failure. Say: “Cool - this tells us what to practice next,” or “Let’s find where it started to feel confusing.”

3) Emphasizing speed (even if you don’t mean to)

Speed pressure is one of the fastest ways to trigger math anxiety. Kids quickly learn: “Math = being fast.” If they’re slower (or careful, or anxious, or neurodivergent), math starts to feel like a trap.

Math anxiety is consistently associated with avoidance and performance drops, and those drops are often largest in situations that feel evaluative (like timed work).

Try instead: Make “thinking well” the goal, not “thinking fast.” If your child’s school uses timed drills, your home can be the place where math is slow, safe, and strategy-based.

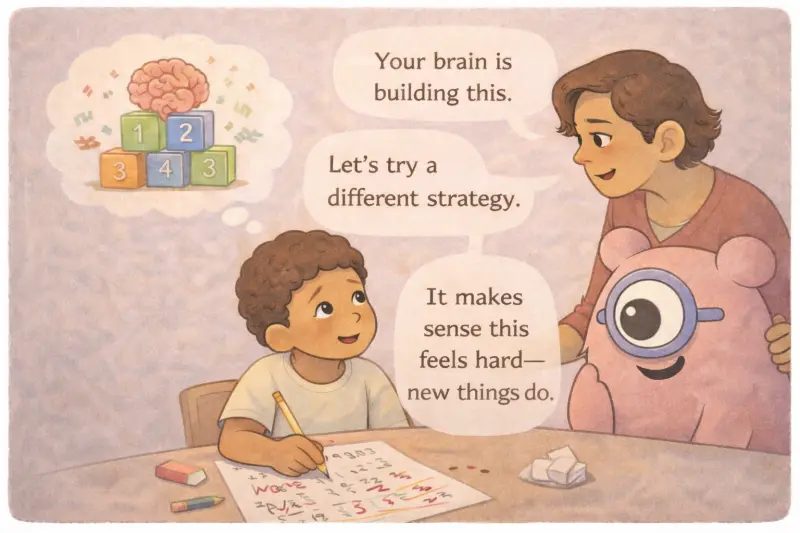

4) Using fixed-mindset language without realizing it

Parents often try to comfort kids by saying things like:

“It’s okay, I was never a math person either.”

“Some people are just not math-brained.”

“You’re more of a reading kid.”

It sounds supportive, but it quietly teaches that math ability is fixed - and that struggle means you don’t have “the gene.” Research on parents’ beliefs is directly relevant here: one study found important links between parents’ mindsets, their beliefs about failure, and children’s math anxiety.

Try instead: Praise strategies, persistence, and noticing. Use: “Your brain is building this,” “Let’s try a different strategy,” or “It makes sense this feels hard - new things do.”

5) “Helping” in a way that becomes intrusive or controlling

This one is painfully common: your child is stuck, you step in to help, and suddenly it becomes your problem to solve. You talk more. You grab the pencil. You correct every step. Your child shuts down or gets angry.

Research is clear that not all homework help is created equal. A 2023 meta-analysis showed that supportive parental involvement - help that preserves a child’s sense of control and thinking - was linked with higher math achievement, while intrusive involvement - correcting, directing, or taking over - was linked with poorer outcomes. For anxiety-prone kids, this distinction matters even more: intrusive help can signal “you can’t do this on your own,” increasing pressure and dependence rather than confidence.

Try instead: Keep your role as a guide, not a driver. Try “Tell me what you’ve tried,” “Where did it start to feel weird?” or “Do you want a hint or do you want to think out loud?”

6) Sending subtle “math is not for you” signals (stereotypes and identity threats)

You might never say “girls aren’t good at math” or “boys don’t read,” but kids pick up identity messages in tiny ways - who gets praised for being “smart,” who gets coached, who gets rescued quickly, and who gets pressure.

Research on stereotype threat shows that when a situation signals “people like you don’t usually do well here,” performance can drop - even when ability is the same. A foundational paper demonstrates this effect in stereotype threat and women’s math performance.

Try instead: Communicate belonging. Say, “Math is for everyone,” and back it up with expectations that are steady and calm: “You can learn this.”

7) Turning homework into a relationship battleground

Kids often experience math homework as more than math. It can feel like: “If I don’t get this, my parent will be disappointed,” or “If I struggle, it means I’m failing,” or “This is going to be a fight.”

When emotions rise, working memory goes down. That’s one reason math anxiety is so sticky - worry takes up mental space that math needs.

Try instead: Protect the relationship first. If the temperature is rising, pause. Take a break. Do one easier problem to rebuild confidence. Or stop and message the teacher: “We hit a wall - can we clarify the strategy?”

What helps most (a simple, research-aligned home approach)

Lower the threat: Remove time pressure at home; make practice feel safe.

Raise autonomy: Let your child make choices (which problem first, hint vs. no hint, break timing).

Shift the goal: From “right answer” to “good thinking.”

Normalize struggle: Treat confusion as part of learning, not a crisis.

Use language that builds: Replace “You’re wrong” with “Let’s check that step.”

These shifts often sound simple, but they can be surprisingly hard to apply in the heat of homework time. Knowing which phrases calm the nervous system - and which ones quietly raise the stakes - can make the difference between a child leaning in or shutting down. That’s especially true for neurodivergent learners, including kids with ADHD, autism, or dyscalculia, who may experience math anxiety more intensely and for different reasons. When parents understand how anxiety, learning differences, and language interact, it becomes easier to support thinking without triggering stress.

If your child’s math struggles look like shutdowns, tears, avoidance, or “I can’t”, that can be a signal that the approach - not effort - is the issue.

Math anxiety is rarely about the math itself. It’s about how a child feels while doing it. When parents shift the tone from pressure to safety - even in small ways - math stops being a test of worth and starts becoming a skill that can grow. Progress doesn’t come from pushing harder; it comes from making space for thinking.

FAQs

Is math anxiety the same as being “bad at math”?

No. Math anxiety is an emotional response that can reduce performance by consuming attention and working memory. Meta-analytic work shows a reliable relationship between math anxiety and lower math achievement, but that doesn’t mean anxious kids lack ability.

Can parents’ math anxiety really transfer to kids?

Yes - especially during homework help. One landmark study found that math-anxious parents who helped frequently had children who learned less math and developed more math anxiety across the school year.

Should I stop helping with math homework?

Not necessarily. The key is how you help. Research distinguishes supportive involvement from intrusive involvement, and intrusive styles are more likely to backfire.

My child freezes under time pressure - what do I do?

Start by removing the clock at home. Many kids freeze not because they don’t know the math, but because time pressure makes their thoughts feel scrambled. Practicing without timers lets your child focus on how to think rather than how fast to respond. Encourage them to talk through their strategy, use drawings or manipulatives, and take pauses when needed. Speed can come later - confidence and understanding come first.

How can I use growth mindset without sounding cheesy?

Keep it concrete: “Show me the step you’re confident about,” “Let’s try another strategy,” or “This is hard because it’s new.” When the words match what your child is actually doing, growth mindset feels supportive instead of performative.

References:

Barroso, C., Ganley, C. M., McGraw, A. L., Geer, E. A., Hart, S. A., & Daucourt, M. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relation between math anxiety and math achievement. Psychological Bulletin. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8300863/

Maloney, E. A., Ramirez, G., Gunderson, E. A., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2015). Intergenerational effects of parents’ math anxiety on children’s math achievement and anxiety. Psychological Science. https://bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/5/1727/files/2019/06/Maloney-Intergenerational-Effects-of-Parents-Math-Anxiety.pdf

Jiang, Q., Li, Y., & Zhang, L. (2023). Parental homework involvement and students’ mathematics achievement: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1218534/full

Xie, F., Li, X., & Wang, C. (2022). The impact of parents’ intelligence mindset on math anxiety of boys and girls: The role of parents’ failure beliefs and evaluation of child’s math performance as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.687136/full

Ashcraft, M. H. (2007). Working memory, math performance, and math anxiety. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 243–248. https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03194059 (overview PDF: https://www.andrews.edu/ceis/gpc/faculty-research/montagano-research/working_memory_math.pdf)

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4–28. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103198913737

Comments

Your comment has been submitted