Why Your Child Can Multiply but Can’t Estimate (And Why That Matters)

TL;DR

Being able to perform calculations (like multiplication) doesn’t guarantee a child has strong estimation or number sense skills. Many children (neurodivergent or not) learn multiplication through rote practice, yet might not grasp magnitude or reasonableness of results.

Estimation is a key part of number sense – an intuitive feel for quantity and magnitude. It helps kids judge if answers are reasonable and apply math in real life (like figuring out if you have enough money without adding every coin).

Number sense and estimation can be developed. Simple activities that build intuitive understanding, such as playing linear number board games or using number lines - and even boost arithmetic skills as a result. Parents and teachers can also explicitly teach estimation strategies, encourage mental math “ballpark” thinking, and use real-world scenarios to practice estimating in a fun way.

Have you noticed that your child can recite multiplication facts or compute exact math facts on paper, yet struggles to make a quick reasonable guess about a quantity or verify if an answer “makes sense”?

They might rattle off that 7 × 8 = 56, but when asked whether 56 seems like a reasonable result for 7 × 8, they get flustered or wildly off track. Or if you ask them to guess how many candies are in a jar without counting, they might get wildly off base, or might not know how to start thinking about this.

In this article, we’ll explore why a child can calculate but not estimate, why that gap matters for their mathematical development, and what it means for kids (and the parents and teachers who support them). We’ll also discuss how estimation ties into a child’s number sense, highlight relevant research, and offer guidance on helping kids build their intuitive math skills.

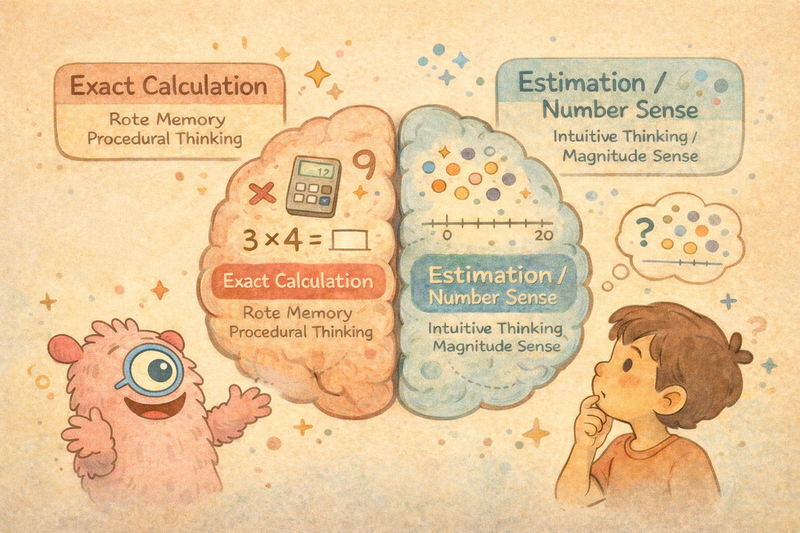

Understanding Calculation vs. Estimation Skills

Exact calculation (like multiplying 27 × 4 to get exactly 108) is a different mental process from estimation (like realizing 27 × 4 should be a bit over 100, without doing precise math). Many children learn to calculate through memorization and step-by-step procedures. Estimation, on the other hand, relies on an intuitive grasp of numbers, sometimes called number sense. It’s the ability to gauge magnitude, make approximate judgments, and even swiftly tell if an answer is “in the right ballpark” without needing to compute it exactly.

Research backs up that these two skills – calculation and estimation – are related but not the same. In a developmental study, psychologists found that children’s performance on exact calculations improved steadily with age (as you’d expect, since older kids know more math facts), but their performance on an estimation task plateaued much earlier – by around 4th grade. Additionally, there was a low correlation between how accurately kids could calculate versus how accurately they could estimate, suggesting these skills at least partly rely on different cognitive abilities.

In short, being a “human calculator” doesn’t automatically make one a good estimator. A child might excel at following learned algorithms or recalling multiplication tables, yet still lack that innate-feeling sense for how large or small a number is.

To put it another way, a child can learn how to multiply (the procedure) without fully understanding what multiplication means in terms of size. They might know 7 × 8 = 56 by heart, but if asked “Is 56 a reasonable answer for 7 groups of 8?” they might be unsure. Procedural knowledge (the steps to get an exact answer) can develop separately from conceptual understanding (grasping the quantity relationships behind those steps). When a child “can multiply but can’t estimate,” it often means the conceptual, number-sense side of math is lagging behind the procedural side.

Why does this gap occur? Sometimes it’s due to teaching emphasis – if instruction and practice have focused heavily on exact computation and less on exploratory number sense activities, estimation skills may not get a chance to flourish. In other cases, the child’s cognitive profile plays a role. Some kids (often neurodivergent learners) naturally lean toward detail-oriented, exact thinking and might find approximation uncomfortable or difficult. Others may have specific deficits in the brain processes that underlie intuitive quantity understanding. In the next sections, we’ll look at some of these factors.

The Importance of Estimation and Number Sense

It’s easy to dismiss estimation as a “nice extra” skill – after all, if a child can compute exactly, why worry if they can ballpark an answer? But in reality, estimation is crucial for deeper mathematical competence and everyday life. Here are a few reasons why strong estimation ability (a sign of healthy number sense) matters:

Catching Mistakes and Understanding Math: Estimation acts as a built-in error checker. If a child mis-remembers a fact or slips up in a calculation, a good sense of scale can alert them that something is off. For example, if they add 7 + 8 and get 15, estimation tells them 15 is close and plausible – but if they got 30, an estimator would sense “30 is way too high for 7 + 8.” Research on symbolic estimation highlights this role: by relying on estimation, people can tell when a result is obviously incorrect without doing the full calculation. This kind of number sense keeps students from blindly trusting every output and encourages them to think critically about quantities.

Applied Problem Solving: Real-world problems rarely present numbers on a neat plate. Whether it’s figuring out if you have enough money at the store, estimating time to complete a task, or doubling a recipe’s ingredients, we constantly use estimation over precision in daily decisions. For students, a classic example is checking work on math problems: does it make sense that 47 × 6 equals 282? If a child can estimate 50 × 6 ≈ 300, they’ll know 282 is reasonable (but that 482 might not be). If they lack this skill, they might accept an absurd answer (or be totally unsure of themselves). Number sense gives context to math – it’s the “common sense” of mathematics that makes numbers feel real.

Foundation for Higher Math: As math progresses, topics like fractions, algebra, and science calculations rely on understanding magnitude and making reasonable approximations. A student who can’t estimate may struggle with concepts like measurement, probability, or judging whether an algebraic answer is of the right order of magnitude. Conversely, a student with strong number sense finds it easier to grasp new concepts because they can relate them to known quantities and make mental connections.

Crucially, a large body of research indicates that early number sense skills predict later math achievement. For instance, in one longitudinal study, children’s number sense in kindergarten (including skills like number comparison and basic estimation) uniquely predicted their math performance in 1st and 3rd grade, even after controlling for general cognitive abilities. The relationship between number sense and math achievement doesn’t fade as kids grow older – if anything, it continues. A study of nearly 5,000 teenagers found that at age 16, teens’ estimation abilities (both on a number-line task and a quick quantity comparison task) were moderately correlated with their math achievement. In other words, those who were better at making numerical estimates tended to be better in math overall. And performance on estimation tasks in adolescence was linked to their math skills measured years earlier in childhood.

This suggests that developing strong estimation and number intuition early on can have lasting benefits.

The flip side is that weak number sense can hinder progress. Math learning isn’t just about memorizing facts; it’s about connecting those facts in a meaningful framework. Children who can multiply mechanically but don’t grasp why 7 × 8 is 56 (for example, that it’s 7 groups of 8, which should be a bit less than 7 × 10) may hit a wall when math requires flexibility. It’s one reason educators and researchers emphasize “building number sense” in the early years – it’s the soil in which the flowers of arithmetic skills grow. Without it, those skills may be brittle. In fact, weak number sense is a hallmark of math learning difficulties.

How to Help Your Child Develop Estimation Skills

If you’ve identified that your child is good at exact calculations but poor at estimation, you’re probably wondering what you can do to help. The goal is to nurture their number sense – to make numbers feel meaningful, not just abstract symbols. Here are some strategies and tips backed by research and educational practice:

Play Number Games: One of the most effective (and fun) ways to build estimation skills is through games that involve numbers and quantities. Research by cognitive scientists has shown that playing linear number board games (think of something like Chutes and Ladders or any board with numbered spaces in order) significantly improves young children’s understanding of numerical magnitudes and their number-line estimation ability.

Use Real-Life Estimation Opportunities: Engage your child in everyday situations where estimation is useful. For example, when grocery shopping, ask them to estimate how much the total bill will be for a few items in the cart, or how many apples you’ve picked without counting. In the kitchen, have them pour out what they think is one cup of water and then measure it together to see how close they were. If you’re driving on a trip, you could play a guessing game like “We’ve been driving for 20 minutes, how far do you think we’ve gone?” followed by checking the odometer. Keep it light and praise the thinking process rather than just accuracy. For instance, “Great guess! You said 50 and it was 47 – that’s very close. How did you come up with that?”

Teach Estimation Strategies Explicitly: Just as we explicitly teach multiplication algorithms, we can teach how to estimate. Some useful strategies include rounding (e.g., to estimate 49 + 53, round to 50 + 50), using benchmark numbers (e.g., recognize that 25 is 1/4 of 100, so 24 is just under that), and chunking (e.g., to estimate items in a picture, group them into smaller clusters and multiply). If a child has trouble with mental math, encourage them to talk through their estimation or even jot a simplification down. For example, if estimating 32 × 18, they could reason aloud: “32 × 18 is roughly 30 × 20, which is 600.” Many children simply haven’t been shown these tactics, assuming that math is always about exact answers.

Visual Aids and Number Lines: Because estimation is closely tied to sensing magnitude, visual representations help make abstract numbers concrete. A blank number line (or number path) is a fantastic tool: ask your child to mark approximately where a given number would fall between two endpoints (e.g., “Put 34 on a line from 0 to 100”). You can do this with percentage, fractions, time scales, etc., appropriate to their level. Over time, they will get a feel for proportional placement. Arrays and area models can also build intuition – for instance, show a 10×10 grid of dots to represent 100, then show a roughly half-filled grid and ask how many dots (around 50). These visuals internalize a sense of scale. Many teachers use number lines and dot grids in the classroom; bringing those into homework time can reinforce what’s learned at school.

Encourage “Reasonableness” Checks: Make it a habit for your child to pause after solving a problem and ask, “Does my answer make sense?” Initially, you may need to model this. Say your child solved a word problem and got an answer of 120 chickens for a small backyard farm scenario. Gently prompt them: “120 chickens… Does that seem like a reasonable number for a small farm? How could we check?” Even if they don’t know, discuss it: maybe compare to something known (“Grandpa’s farm has 10 chickens, so 120 is much bigger; maybe the problem intended a smaller number”). The idea is not to criticize mistakes but to train their estimation reflex. With time, they’ll internalize this habit. It’s a skill that will serve them not just in math class but in life.

Leverage Technology Thoughtfully: There are many apps and math games designed to improve number sense and estimation. For instance, apps that have children quickly estimate sums or place numbers on a slider can gamify the practice. If your child enjoys screen time, incorporating a math game can turn practice into play. Just ensure it’s designed well (based on educational research) and not purely drill. The goal is to develop intuition, so games that adapt to the child’s level and nudge them to refine their estimates (rather than just multiple-choice or speed drills) are ideal. Always preview an app or game to see if it aligns with the skills you want to build.

In Monster Math - the Rounding Rescue game helps kids practice rounding as a foundation to estimation.

Above all, keep a positive attitude about estimation. Many adults have math anxiety and might inadvertently pass on the message that “math is hard” or “I’m just not a math person.” When working on estimation, frame it as a curiosity: “Let’s see who can get closest!”, “This is like being a detective with numbers.” If your child gives a wildly off estimate, resist any urge to scold – instead, treat it as a learning moment: “Wow, you guessed 200 and it turned out to be 50. 200 was a lot more than 50. How might we guess differently next time?” The aim is to make your child feel safe trying an estimate and realizing that improving at estimation is just like improving at a sport or instrument – it comes with practice and insight, not because someone is inherently “bad at it.”

Conclusion

Every child’s mind is unique, and the balance between precise calculation and rough estimation skills will vary from one learner to another. If your child can multiply but can’t estimate, it’s a signal worth paying attention to. Often it means they’ve learned the letters of math (the procedures) but not the full language (the meaning behind the numbers). The encouraging news is that number sense and estimation are very much teachable. With understanding, patience, and the right strategies, you can help transform estimation from a daunting guess into a confident insight.

FAQs

Q: My child is in 4th grade and can do multiplication and division, but struggles with estimation. Is this normal or should I be concerned?

A: Some difficulty with estimation around 4th grade is not uncommon. In fact, research shows that by around 4th grade, many children’s estimation skills on certain tasks plateau, meaning they don’t automatically keep improving without deliberate practice. However, if your child’s estimation skills are significantly lagging – for example, they have no sense if an answer is off by a large margin – it’s worth giving it attention. It might be simply that estimation wasn’t practiced enough, or it could be a sign of an underlying number sense weakness (as seen in dyscalculia). Start by working on estimation in a fun, low-pressure way (use some of the strategies above). If your child makes progress with practice, that’s a good sign. If they continue to struggle or if it’s causing them anxiety in math, consider getting an evaluation for a math learning difficulty. Early support can help get them on track.

Q: What does research say about improving number sense? Can it really be taught, or is it something you’re born with?

A: Both! There is a natural, innate component to number sense – even infants can distinguish between quantities in a rough way, and this Approximate Number System (ANS) becomes more refined as children grow (and is present in all humans to some degree). However, like many innate abilities (think of musical talent or language ability), the environment and practice play a huge role in how well it develops. Research definitely shows it can be improved. For example, studies have found that simple interventions like playing numerical board games or engaging in targeted estimation practice lead to measurable gains in children’s estimation accuracy.

In short, while kids may start with different baseline aptitudes for number sense, experience and teaching can significantly enhance those skills. The brain is plastic – practicing estimation and number reasoning strengthens the neural networks involved.

So even if a child seems to lack number sense at first, don’t despair; the right activities can grow that capacity. This is why early childhood educators use things like number lines, counting games, and estimation jars – they are effectively training number sense. And for older kids, it’s not too late either: you can always improve by practicing these skills in engaging ways.

Q: My child gets frustrated because they want the exact answer and feel like estimation is “guessing” or a waste of time. How do I change this mindset?

A: It’s common, especially for kids who have been praised for getting things “right,” to feel uneasy about an activity where there isn’t one exact answer. To help shift this mindset, try the following:

Emphasize the purpose of estimation: Explain that even adults use estimation all the time because it saves effort and helps catch mistakes. Make it like a superpower: “Estimation is a quick way to get insight without doing all the work. It’s like a shortcut that smart people use to check their thinking.” Sometimes kids respond when they see the utility.

Make it a game or challenge: Turn estimation into a friendly competition or game where being close is the fun. For instance, have everyone in the family guess something (like the number of popcorn kernels that popped) and then see who was closest. This makes it less about right/wrong and more about honing a skill.

Praise the process: When your child makes an effort to estimate, applaud their reasoning. If they say “I guessed 100 because that’s 10 groups of 10,” focus on that logical approach rather than the outcome. You might respond, “I love how you broke it down into tens, that’s exactly how mathematicians estimate!”

Connect it to their interests: If your child loves certainty, perhaps they enjoy science or facts. Point out that even in science, we make hypotheses (which are essentially estimates or educated guesses) and then test them. Or if they like video games, note how gamers estimate how many resources they need before actually collecting them, etc.

Gradually bridge to exact answers: One technique is to always follow an estimation task with an exact answer so they see the relationship. For example, ask them to estimate the sum of 48 + 35, discuss their estimate (say they guess ~80), and then have them do the exact addition (48 + 35 = 83). When they see the estimate was useful and close, it reinforces that it wasn’t pointless – it gave a preview. If their estimate was off, discuss why without judgment.

Model comfort with uncertainty: Children often take cues from adults. If you show that you sometimes just estimate and are fine not knowing an exact number, they learn it’s okay. For example, say out loud, “Hm, I’m not sure exactly how many people are at the park, but I’d estimate around 30. That’s enough to know it’s pretty crowded.” This normalizes approximation as a valid way of thinking.

Changing a mindset takes time. Be patient and keep exposing them to situations where estimation proves its value. Over time, they’ll likely develop more confidence and maybe even enjoyment in using their intuition alongside their precise skills.

References

Ganor-Stern, D. (2018). Do Exact Calculation and Computation Estimation Reflect the Same Skills? Developmental and Individual Differences Perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology

Szkudlarek, E. & Brannon, E.M. (2017). Number Sense and Mathematics: Which, When and How? Developmental Science

Gilmore, C.K., Göbel, S.M., & Inglis, M. (2018). (Study of 4,984 students) Symbolic and nonsymbolic estimation: associations with mathematics in a large cohort of 16-year-olds.